While it’s a cliché to begin with a quote, I’d like to do so ironically because Kishori Amonkar, the subject of this piece, was anything but “cliché.” In an interview with photographer Raghu Rai, she had said, “Even if there is pain or suffering, giving it beautifully is art.”

Today, we are more than typically aware about the growing pains of our globalized, interconnected world. I hope to meditate on the life and work of Kishori Amonkar, or Kishori-tai, as a search for how we may mindfully, and dare I say “artistically,” navigate through our brave new world towards a more beautiful one.

Earlier this month, the reigning diva of Hindustani Classical music, “Gaanasaraswati” Kishori Amonkar – the singing goddess – passed away in her sleep. Like many, I awoke to this news and received it bitterly. A flood of feelings, memories, and (of course) music began to fill the new void of what has remained the haunting enigma of Kishori-tai. Her death is a reminder of the creative responsibility that our suffering world must reconcile; to mitigate the tensions between past and present for a better future. Let me explain.

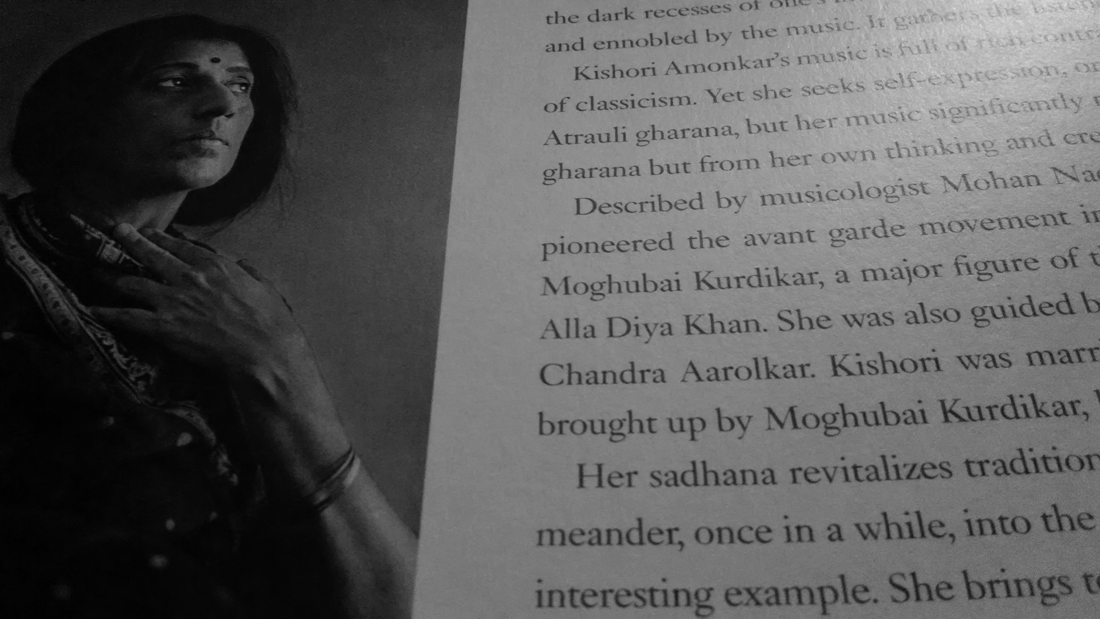

An excerpt from a chapter on Kishori Amonkar in Raghu Rai’s book.

Dissonance in the Digital Age

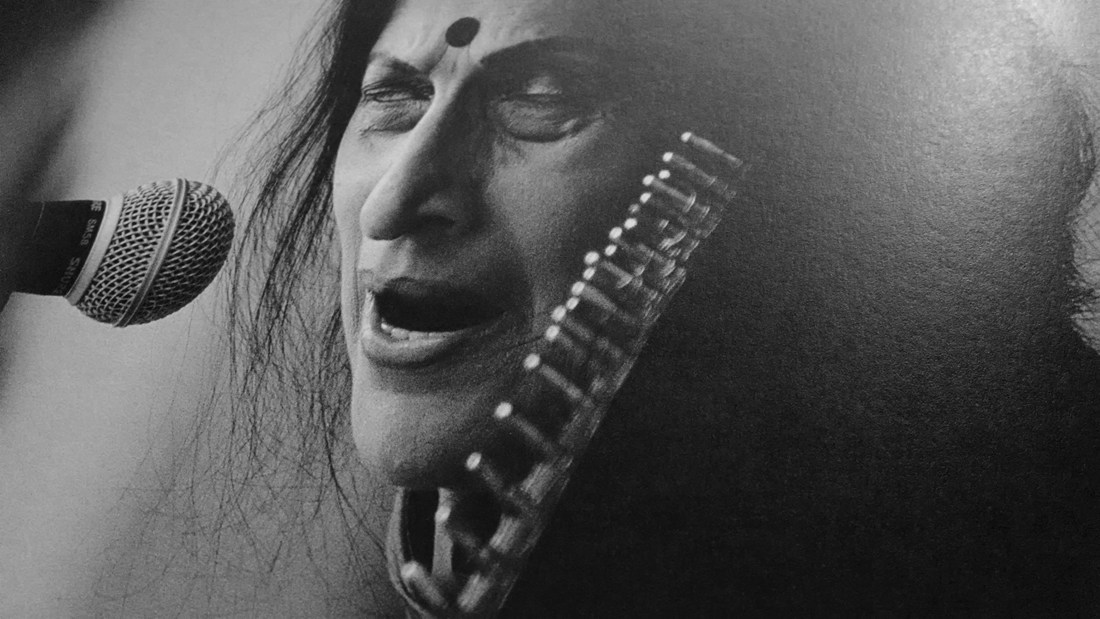

At 11-years-old in 2003, I first heard Kishori-tai live at Mumbai’s National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) on a winter evening. Naturally, she was incredibly late. A spontaneous and stubborn applause from the audience beckoned her onto stage from the green room. She emerged soon after. After bowing her body fully to the audience in gratitude for the gesture, she commenced her performance with Raag Shuddha Kalyan followed by Raag Basanti Kedar. Arguably, she sings these raags better than anyone. From that night on, I was forever changed by her brilliance. The subtlety of cascading harmonies, opulence of sensitive expressions, and rich intelligence of her music drowned me in an ambiance of unimaginable creativity; an unconditional submission to the miraculous glory of sound.

My cherished memory feels rarer as our world moves towards sensibilities that leave little space for artists like Kishori-tai. Emotional sacrifice, depth, and expressionism have little to do with cultures governed by viral trends. Ironically, again, our densely uncertain times could benefit from the imagination of artists like Kishori-tai. If the critic’s task is to cast light upon the shadows of our times, then it is an artist’s task to create light from darkness. Let us cast light upon Kishori Amonkar so we may begin the task of what comedian Dave Chappelle describes as a “reconciliation of paradox.”

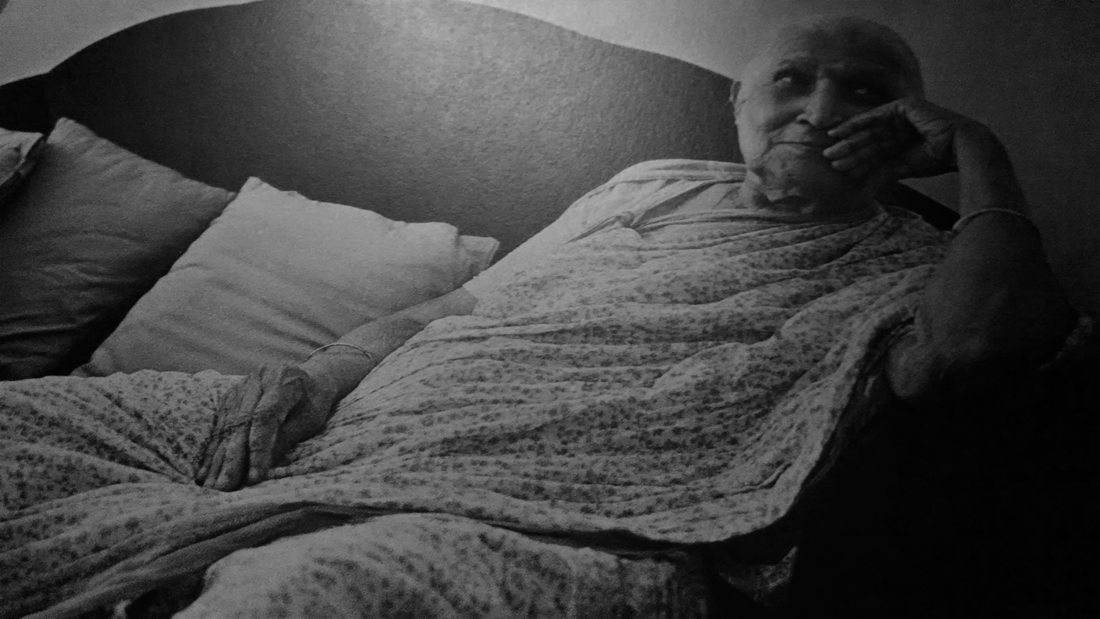

Mogubai Kurdikar, photographed by Raghu Rai.

Ancient Voice, Modern Vision

We have the persisting burden of building resonance in our dissonant world. The resolutely stubborn vision of a creative voice can lend an innovative perspective on our mundanities and ambiguities. As someone who earned an inimitable status in the music world, Kishori-tai is the perfect model for our task.

Kishori-tai’s achievements are a response to the struggles that her mother, Mogubai Kurdikar, had endured. Mogubai was one of the great Indian musicians of the past century. This is largely because she endured a life burdened by poverty, competition, and loss (when the world was meaner to single mothers, female musicians, and ambitious women). Revolutionarily, she left a lasting matrilineal tradition of vocalists in a field that has been overwhelmingly patrilineal. Kishori-tai inherited the catch-22 of benefiting from and overcoming these accomplishments to establish her own merits. She succeeded in this daunting task by advancing and transcending much of what characterized the music and style of Mogubai and her pedagogical contemporaries, Kesarbai Kerkar and Laximibai Jadhav.

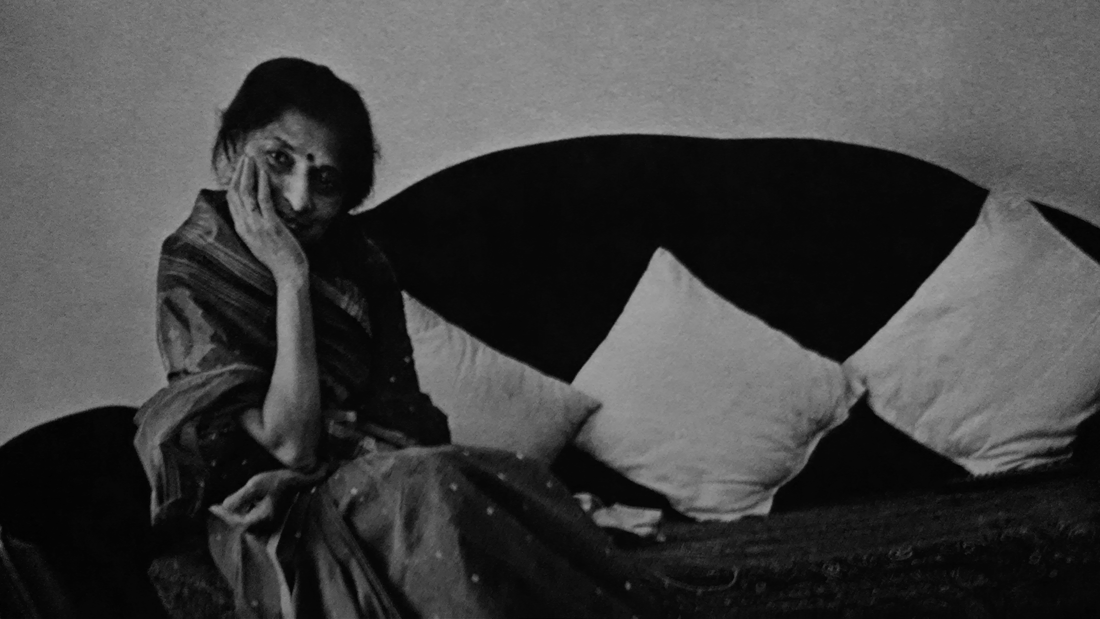

Kishori Amonkar in contemplation, photographed by Raghu Rai.

For instance, examine how Kishori-tai has rendered Raag Basanti Kedar distinctly from Mogubai, Kesarbai, and Laxmibai. She has gravitated away from the aesthetic sensibilities of “forceful” and “aggressive” singing that their patriarch, Alladiya Khan, had advocated. Instead, Kishori-tai’s rendition is very emotional, “feminine” (by how it capitalizes on expressions atypical of a historically “male” style), patient, and subtle. Kishori-tai’s now-canonical musical approach had at that time shaken the very establishment of ideal musical aestheticism. To challenge these values was to invalidate the patriarchal, conservative, and elitist tastes that had dominated the classical music intelligentsia at the time (and in many ways still do).

If Mogubai, Kesarbai, and Laximibai were the Dutch Masters of classical music, then Kishori-tai was its Van Gogh. Like Van Gogh, her art was perpetuated by obsession, torment, and passion to capture the unexpressed. The fruits of this arduous path to distinction, for Kishori-tai, distanced her from the midst of her titanic predecessors. In many ways, Kishori-tai’s brilliance is a consequence of Mogubai’s disciplinarianism, Kesarbai’s competitiveness, and Laxmibai’s premature death. Over many decades, Kishori-tai’s music has been described as “pure,” “unparalleled,” and “evergreen.”

But, the opposite has also been said of Kishori-tai; that her music is too avant-garde, experimental, and moody. Her infamously inelegant on-stage tantrums and demands have been the subject of connoisseur gossip for decades. Although understood as a torchbearer of the Jaipur-Atrauli legacy of classical music, she has intelligently assimilated the arts and sciences of non-Jaipur-Atrauli musicians she has learned from, most notably Anjanibai Malpekar, Anwar Hussain Khan, and Sharadchandra Arolkar. Even some raags that Kishori-tai sings have changed characteristically across time in curious, almost irrational ways. For example, Raag Bilaskhani Todi would sound wholly different from one month to the next, going from a Raag Jaunpuri twist to a Raag Bhairavi one. With such ongoing shifts, one can lose track of how (and whether) Kishori-tai balances theoretical sanctity and artistic license.

I mention these peculiarities to suggest that within the harmonious body of Kishori-tai’s image are included many inconsistencies that, ultimately, compose a richer, more imaginative entity. In her musical journey, Kishori-tai was, above all, seeking authenticity. Concerns of legitimacy, ingenuity, and power were merely unintended consequences of a much nobler and unpopular cause; to do justice to her lived experiences – good and bad. Art and science in service of spirit.

Kishori Amonkar entranced, photographed by Raghu Rai.

A Pitch for Progress

The systems and strategies of meaning that have served our world for so long – the stories that orient our interrelations – no longer work. “Black” and “white” cannot remain in their existing definitions when the world is being enveloped in an ambiguity of “gray” – even “color.” But, as Albert Einstein observed, “No problem can be solved at the same level of consciousness that created it.” Rather than struggling to govern a language capable of traversing the hurdles of our impatient world, we require a transcendental approach that enables us to wrestle with our demons and empower the better angels of our nature. Kishori-tai’s music is meaningful because she put this into practice. She sought to resolve and debate her paradoxes to live deliberately (as opposed to symbolically).

Kishori Amonkar marched to her own tune. Aspirations for political correctness, creative influence, and common sensibility deter us from a far-sighted strategy aimed at solving our debilitating global problems. We must place greater importance on a diversity of ideas, not just bodies. We must seek to invalidate our pasts, not compensate for them. We must seek to be expressed, not be impressed. We must appreciate that our voices can carry a lot of weight. Kishori-tai proved that, through melody, harmony, and history. Thus, our persisting question: what are we singing toward?

We find ourselves with the same predicament that Kishori-tai had faced. We are burdened with the legacy of our ancestors with all their vices and virtues. We are suffocated by obsessions about what is common and decent, struggling to find what is “right” and “just.” We seek to escape the mistakes of history, eager to seize a better future within our grasp. We find ourselves in a war with time, space, and ideas, in a quest for an image of who we should be. So, take Kishori-tai’s advice. Stop fighting with haunting images and simply be hauntingly imaginative.

No Comments